Following the Text Gradient at Scale

RL Throws Away Almost Everything Evaluators Have to Say

When you get feedback on your work, it usually tells you what went wrong and how to fix it. But existing reinforcement learning (RL) algorithms throw most of that information away; it compresses potentially rich feedback into a single number, a reward1, then tries to learn by correlating rewards with actions across hundreds or thousands of attempts. We do this because our algorithms were designed for scalar supervision, not because of a fundamental constraint in learning from experience2.

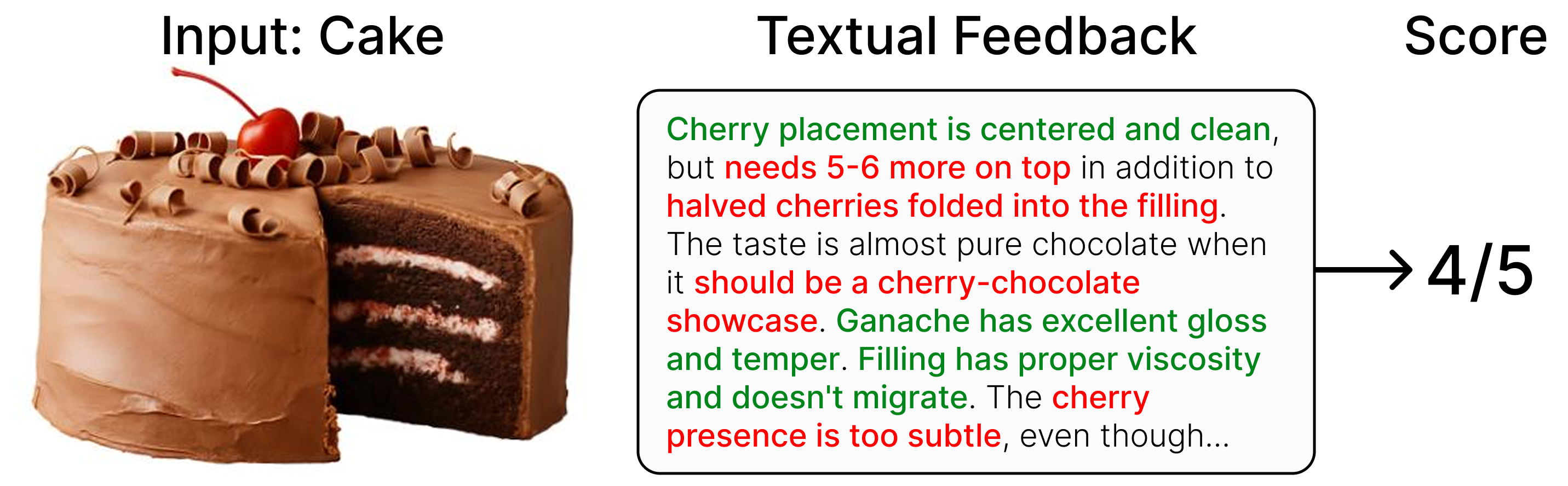

To illustrate this, let’s consider a simple example. Suppose you’re judging cakes. You take a bite, you like the shavings on top, the ganache is perfectly tempered, but you want way more cherries throughout. Yet you only record: “4/5.” The baker learns nothing about the cherry distribution or what else worked well, only that this cake scored higher than a 3. If this is the only information you provide, the baker will likely have to do a lot more baking to figure out what you actually want. 3

More generally, an expert given a candidate solution can articulate specific failure modes, causal mechanisms, and concrete fixes. Full verbal feedback for the cake above would contain far more actionable information than the numerical score “4/5”. The baker can confidently keep the parts of the cake that worked well, rather than blindly exploring recipe variations. This is the core insight: rich feedback enables targeted improvements rather than random exploration, resulting in fewer trials to achieve a better outcome.

This striking mismatch between the information available and the information used by RL has been aptly described as sucking supervision through a straw: you run minutes of rollout and compress it all into a final reward signal broadcast across the entire trajectory. This scalar bottleneck is becoming increasingly costly in the tasks we’re deploying LLMs on: for example, research agents run 5-30 minutes per task. Each run produces rich diagnostic logs—tool calls, intermediate reasoning, error traces—all of which are collapsed into a single scalar that discards the causal signal of where and why things failed. While rich feedback requires a bit more work from the evaluator, they’ve already done the reasoning; we’re just asking them to write it down. When rollouts themselves are expensive, the marginal annotation cost is small relative to the sample-efficiency gains we can achieve with richer feedback.

In this post, we survey an emerging learning paradigm that fully embraces all the feedback an environment has to offer—avoiding the scalar bottleneck of RL—and discuss our recent work called Feedback Descent (check out the paper here), which outperforms specialized RL methods in challenging optimization domains such as molecular design and prompt optimization.

From Scalar Rewards to Text-Based Optimization

A growing body of work hints at an alternative to reward-based learning: directly using rich feedback to guide model improvement. Given a textual artifact (e.g., a prompt, source code, molecule specs), we can often provide natural-language explanations of how to improve it. That explanation is already a form of supervision. Rather than compressing it into a single number, we can feed it back into the system during the update.

In recent work, two broad patterns have emerged around this principle:

- Critique-based or “text gradient” methods. The model proposes an artifact and receives a natural-language critique of its errors or omissions. The critique explicitly suggests a direction of improvement: adjust the retrieval query, remove this redundancy, change the control flow, etc. A revised artifact is then produced by editing the original in line with the critique. This pattern appears in systems such as Self-Refine, APO, Trace, and TextGrad.

- Evolutionary methods. Instead of iteratively editing a single artifact, these methods maintain a population of artifacts. Language models generate mutations and recombinations conditioned on the current population, and evaluators select the better ones. Iterating this variation-selection loop gradually shifts the population toward higher-performing algorithms or designs, as in EvoPrompt, GEPA, and AlphaEvolve/OpenEvolve, and has driven novel mathematical discoveries.

Both lines demonstrate the same underlying principle: textual feedback can serve as structured supervision, often far more informative than scalar rewards. In the remainder of this post, we build a single, domain-agnostic loop around the two primitives these approaches rely on: an evaluator that produces structured feedback, and an editor that turns accumulated feedback on the current best candidates into concrete revisions. We will demonstrate how this loop can sustain meaningful improvement for up to 1000 iterations, far beyond the stability range of standard self-refinement methods.

Example Domain: Drug Discovery

Let’s make this concrete with a problem where the stakes are high and real-world evaluation is expensive: computational drug discovery. The goal is to find small molecules that bind strongly to a target protein, a critical first step in developing new therapeutics. We can navigate the (huge) space of possible molecules using a standard text representation called SMILES: for example, COCCc1ccc(OCC(O)CNC(C)C)cc1 is metoprolol, one of the most prescribed blockers of ADRB1 (one of our target proteins). Given a target protein, docking simulators can give us a proxy score for binding affinity; if we treat this as a standard RL-style optimization problem, the environment returns only a single scalar reward for each SMILES:

- Molecule 1 (

O=C(O)C1=CC=CC=C2C=CCCCCCN1C(=O)c1cccc(c1)C2): Reward = 5.037 - Molecule 2 (

COCCc1ccc(OCC(O)CNC(C)C)cc1): Reward = 4.236

A scalar reward like this hides almost everything about why one molecule is better than the other. But nothing stops us from designing evaluators that expose a much richer structure. For each candidate, the evaluator can report a detailed breakdown of its molecular properties. Below is a small subset of RDKit-computed features for these two molecules4:

| Property | Molecule 1 | Molecule 2 | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core scaffold | macrocycle | benzene | Rigid fused system vs. flexible benzene |

| Docking score | −6.8 | −7.1 | Molecule 1 binds weaker |

| Drug-likeness (QED) | 0.824 | 0.714 | Molecule 1 is more drug-like |

| Basic amines | 0 | 1 | No salt bridge with Asp138—explains weak binding |

| Rotatable bonds | 1 | 9 | Rigidity boosts QED but pre-organizes wrong pose |

| LogP | 4.3 | 1.6 | Too lipophilic, solubility risk |

A medicinal chemist would be able to look through this table and reason almost immediately:

- Molecule 1 has a better overall drug-likeness, but a worse docking score.

- Molecule 1’s lack of basic amines explains the weak docking score. Molecule 2 binds better because it forms a salt bridge.

- A promising candidate would merge the strengths of both: keep the favorable macrocycle scaffold of Molecule 1, but introduce a basic amine.

The scalar reward reveals none of this structure, but the rich feedback exposes a clear path forward. This is precisely the kind of targeted, interpretable guidance that feedback-driven optimization can exploit (and what traditional scalar-based RL discards).

The Feedback Descent Algorithm

Having seen how rich feedback can reveal an actionable structure beyond what a scalar reward can, we now describe the general framework that turns this idea into a scalable optimization procedure.

Feedback Descent is a domain-agnostic loop built from two components:

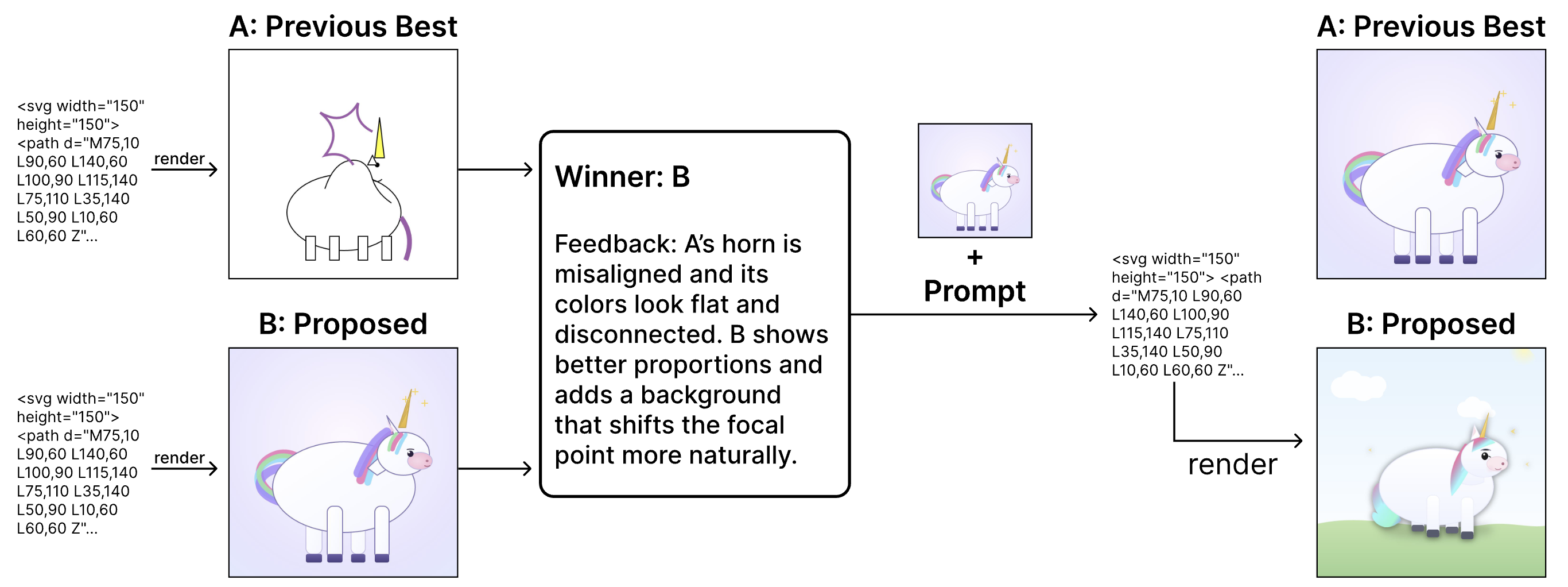

- Evaluators: rich feedback instead of scalars. An evaluator (an LLM judge, a programmatic tool, or even a human) provides natural-language feedback describing what worked and what didn’t. For different domains, the feedback may include chemical properties and nearest neighbors in a database (molecules), missing structure or aesthetic flaws (SVG images), or reasoning errors and unmet conditions (prompts). The evaluator exposes why an artifact performs the way it does, rather than just whether it did well or poorly.

- Editors: revisions guided by accumulated feedback. The editor is an LLM that takes the top candidates and the evaluator’s accumulated feedback and outputs a revised version. This is the descent step: the LLM implicitly incorporates the strongest signals from prior feedback into its following proposal.

Feedback Descent alternates these two steps while maintaining a small frontier of top-performing candidates. For each newly proposed candidate, the evaluator provides feedback. We aggregate all prior feedback and pass it to the editor, and the editor proposes a new candidate:

Over many iterations, the candidate population continually improves as useful feedback accumulates and unproductive directions are discarded. Since both evaluation and editing occur entirely through text, the same loop transfers cleanly across domains, with the only domain-specific component being the evaluator that supplies feedback.

Does Feedback Descent Work?

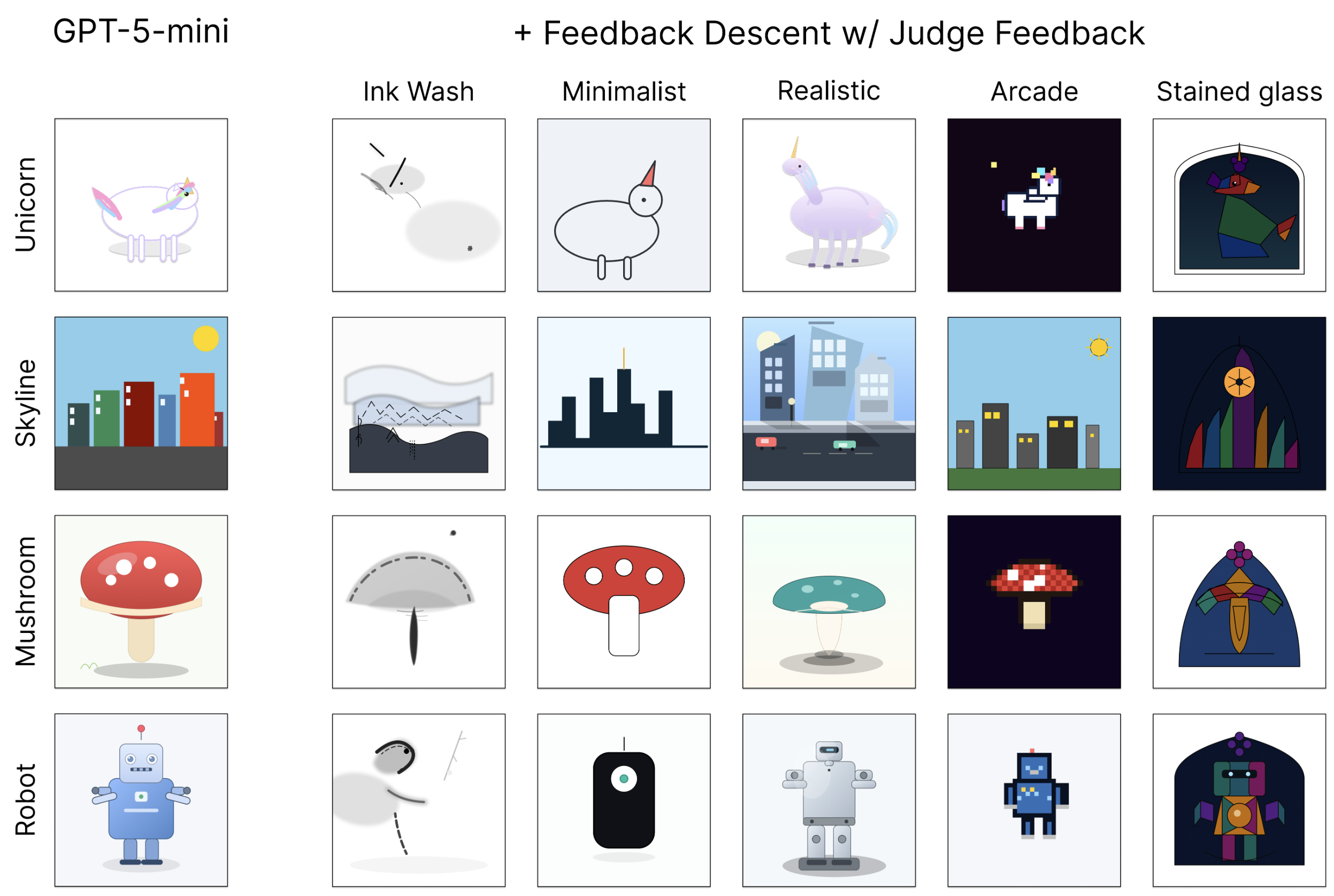

We applied the same Feedback Descent framework to three fundamentally different domains: molecular design, SVG image optimization, and prompt optimization.

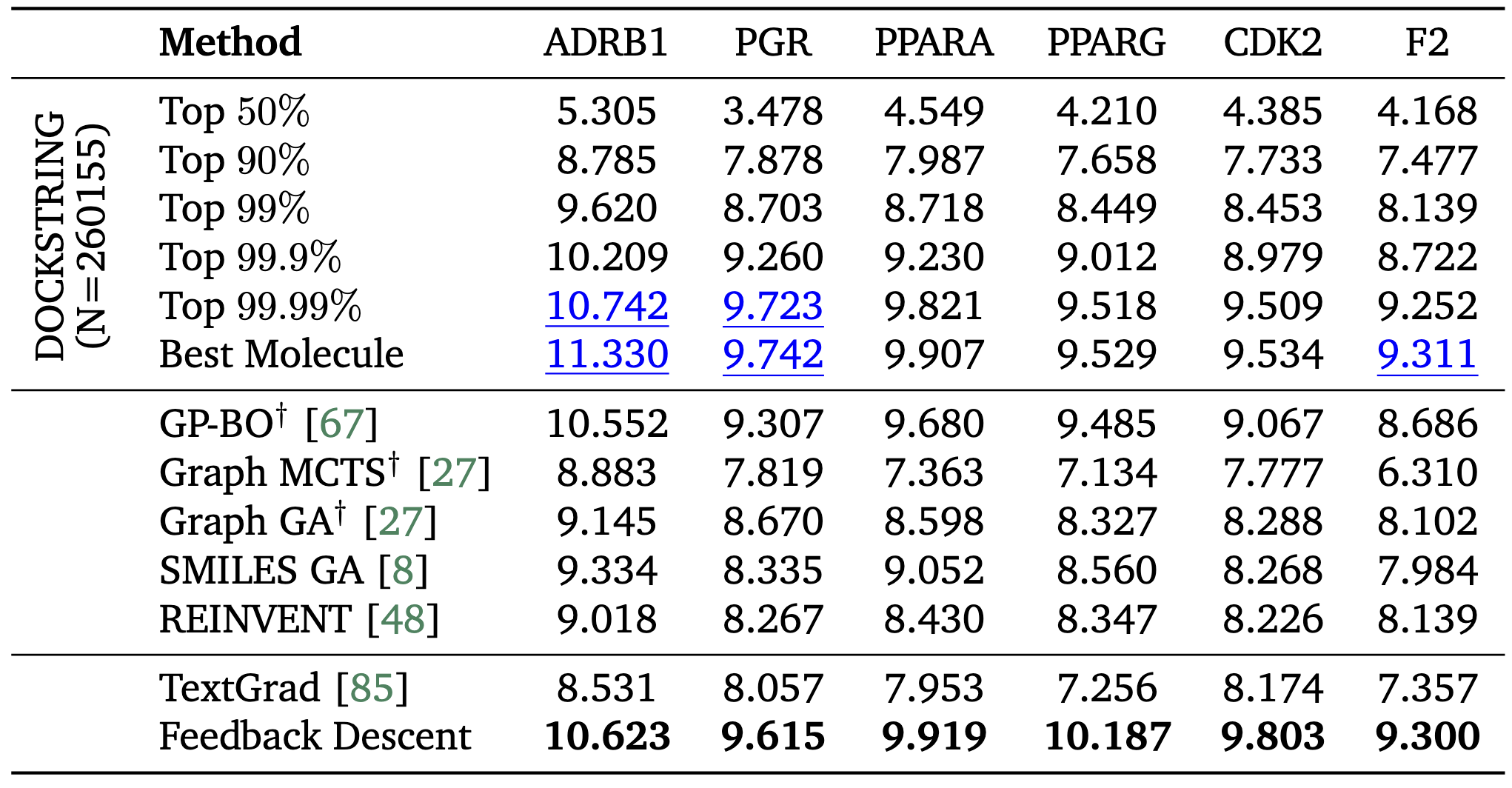

Molecular Design. We compared Feedback Descent with specialized graph-based molecular optimizers that explicitly encode chemical structures, as well as REINVENT, a reinforcement learning method specifically designed for molecular optimization. Feedback Descent, operating purely on text representations (SMILES strings), matched or exceeded these specialized methods. On multiple targets, our text-based approach identified molecules surpassing the 99.9th percentile of DOCKSTRING’s 260,000-compound database. In several cases, we matched or exceeded the best molecule in the entire database. In this domain, Feedback Descent achieved an average 3.8x reduction in docking calls relative to reinforcement learning (REINVENT).

SVG Optimization. Starting from basic SVG drawings, Feedback Descent consistently improved designs through iterative visual critique. After just five iterations, designs reliably outperformed a baseline that conditioned on the judge prompt verbatim, demonstrating a generator-verifier gap where iterative feedback elicits better outputs from the same model.

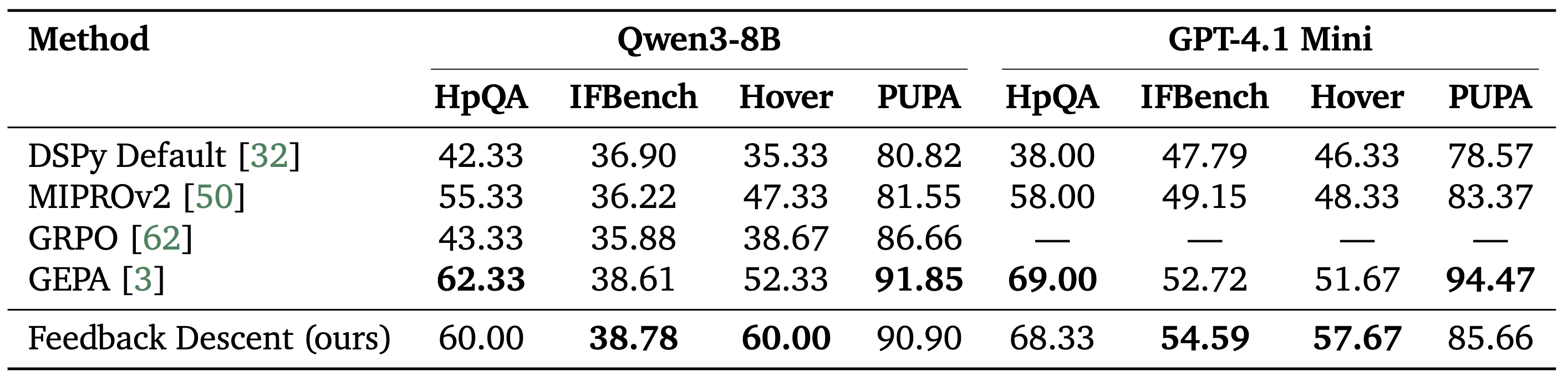

Prompt Optimization. On four diverse tasks (multi-hop reasoning, instruction following, privacy-aware delegation, and retrieval verification), Feedback Descent achieved competitive performance with GEPA, the state-of-the-art prompt optimization method, while outperforming GRPO, a reinforcement learning baseline.

Together, these results demonstrate that the same evaluator-editor loop can drive continual improvement in domains that differ in representation, evaluation, and failure modes. The only requirement is that we can obtain and express informative feedback in text; no task-specific optimizers, mutation rules, or architectural changes are needed. The informative signal is carried by the textual feedback itself, and the editor LLM uses this feedback to guide its next revisions through in-context learning.

Is Text a Viable Medium for Learning?

In conventional gradient-based learning, progress accumulates in the model’s weights. These parameters absorb broad statistical structures and give models the general competence we rely on. But weight updates are not the only place where learning can happen.

Text-based optimization suggests a complementary substrate: semantic space.

This is especially promising for continual learning, where parameter updates often struggle because the knowledge stored inside the weights is highly entangled, new updates risk catastrophic forgetting and require careful regularization or access to past data. In contrast, textual artifacts persist. They accumulate naturally as the system operates, and grow in a form that LLMs can readily condition on. New feedback can be integrated immediately without retraining the underlying model.

This is early territory. We don’t yet know the full limits of what can be stored or refined in semantic space. But the evidence so far suggests that text-level artifacts can absorb detailed feedback from the environment and unlock forms of improvement that are difficult or inefficient to achieve through weight updates alone. Understanding how to organize and scale this semantic layer, and how to integrate it cleanly with parameter learning, is an exciting direction for future work.

This post is based on our recent work “Feedback Descent: Open-Ended Text Optimization via Pairwise Comparison.”

We thank Anikait Singh, Henrik Marklund, Mert Yuksekgonul, Jubayer Ibn Hamid, Allen Nie, Omar Khattab, Sergey Levine, SAIL blog editors (James Burgess, Megha Srivastava), and anonymous ICLR reviewers for their helpful feedback on earlier drafts.

Footnotes

-

Dense rewards can help with temporal credit assignment, but don’t address the information bottleneck; a scalar at every step still doesn’t tell you what went wrong or how to fix it. Even when dense rewards are available, they’re notoriously hard to design well and prone to reward hacking. In practice, rewards for LLM post-training are usually sparse (outcome-based verification, human preferences), making this limitation especially acute. ↩

-

Here, we’re primarily talking about policy gradients since that is the dominant paradigm for LLM post-training. Value-based methods are more sample-efficient because they propagate credit across time. However, this addresses temporal credit assignment while leaving the information bottleneck intact. This gap is exponential: Du et al. show that even in settings where value functions are perfectly representable, RL requires exponentially more samples than richer supervision (i.e., imitation learning). ↩

-

This is, of course, a reference to Yann LeCun’s cake analogy. One “cherry on top” is too little for some appetites 🙁 ↩

-

For clarity, we only show condensed feedback from two molecules in this table. In practice, the Feedback Descent system is shown full feedback on all top-k molecules proposed so far. ↩